The metaverse’s biggest unknown: Where we go from here

Technologies at large scale don’t behave the same as technologies at smaller scales. I think about that a lot regarding the evolution of the internet.

I think about that with the metaverse.

The idea of a new immersive interactive platform for worldwide communication, most visibly brought back into life by Meta (aka Facebook), already looks like it’s headed for trouble.

Waves of tech layoffs, including thousands at Meta, create a sense that the dream may already be over. This happened with the internet before: the first dot com bubble, for instance. Some ideas died, others survived, and new ones came afterwards that no one predicted.

But – if the concepts that infuse the metaverse truly take off, I don’t think the evolutions after that are easy to predict. They’re bound to be different. The rise of social media transformed human communication, as did the phone. So did the internet.

Different phases, different impacts.

The metaverse is clearly made of pieces we already recognize, but I’m also reminded of the old David Letterman interview with Bill Gates where he describes the internet – and every part sounds like something you could already get somewhere else. Why listen to a stream of a baseball game when there’s the radio?

Also: Metaverse: Momentum is building, but companies are still staying cautious

I think there’s something of that situation now with the metaverse. If it’s a more immersive experience, why not just use a large TV and headphones? If it’s a virtual world, why not just play a video game?

I don’t think it’s that easy. Or that simple.

I’ve been covering VR and AR for about 10 years at CNET, or even longer. One of my very first blog posts back in 2009 when I started was about augmented reality and magic. At that point, I had already spent decades thinking about VR, all the way back to high school. I wrote plays about chat rooms and online role-playing games. The future seemed like it was getting here late.

In 2022, I’m mostly still waiting for the future. But at other times I realize that future has been happening all along, curling around me. VR isn’t the future now. It’s something my friends and I have used for years.

Virtual reality is a concept most people either find interesting or simply dismiss. They get it or they say, “I’d never use that, why bother, and why would anyone else?”

I don’t use the Meta Quest 2 in my office every day, or even every other day. But for an hour or so every once in a while, it still offers up an experience that, to me, I can’t get elsewhere.

During the pandemic, VR became a place where I’d escape for a bit and work out to Beat Saber, let loose and feel like I had my own expansive place to be. But it isn’t the games or the puzzle-like escape rooms that compel me most now, it’s social moments with people I know and meet with there. A handful of college friends – who approached me about playing together in VR, not the other way around – started meeting up for mini golf, or role-playing games in a tabletop app called Demeo. I know their voices and remember their faces. When I play with them as cartoon masks, I project them in much like I imagine people on a voice call. But I remember them, later, as moments almost like I was there with them.

I’ve also been fortunate enough to join with a few other people once a week and explore acting and performance using avatars, using Microsoft’s virtual worlds app AltspaceVR on the Quest 2. I’ve never met any of my fellow performers before. We talk, explore movement, notice how our emotions carry over to our virtual cartoon selves – and when they don’t. We learn how to express better in these spaces. I remember every session like we’ve all gathered, in a large empty stage, to really be there.

In this way, VR already bends time and space and plays with the way my memories work. It’s made me convinced it will only happen more.

But the hardware and software that’s being used right now, including Meta’s new Quest Pro, just aren’t good enough yet to handle the challenge. They do, however, show glimmers of possibilities. Apple’s expected VR headset, along with other devices coming in the next year, could try to answer a need for better gadgets. In the meantime, however, the bigger challenge is making frameworks that can knit together all the software and devices we already use and making better room for these new peripherals too.

The metaverse is a new term as far as business strategy goes, and an old one for sci-fi readers of Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash. The familiar feeling of it all can make it seem like a rehash, or even a scam. Parts of it undoubtedly are. But, going back to the start of the World Wide Web, it was exactly the same. Some websites that were part of the first dot-com bubble crashed and burned. A few stuck around.

Also: What the metaverse means for you and your customers

The internet has kept changing, evolving from static websites to streaming video, social media, apps on phones, services that knit between platforms. It’s what makes me wonder what the metaverse will truly be in another 10 or 15 years. Just because a technology exists doesn’t mean it’s perfected. If this is the dawn of a new phase of computing, will we even understand it by the time it’s spread out and widely adopted?

When, not if

It’s not interesting anymore to ask: ‘What if the metaverse happens?’

Instead, ask: ‘What happens when the metaverse happens?’

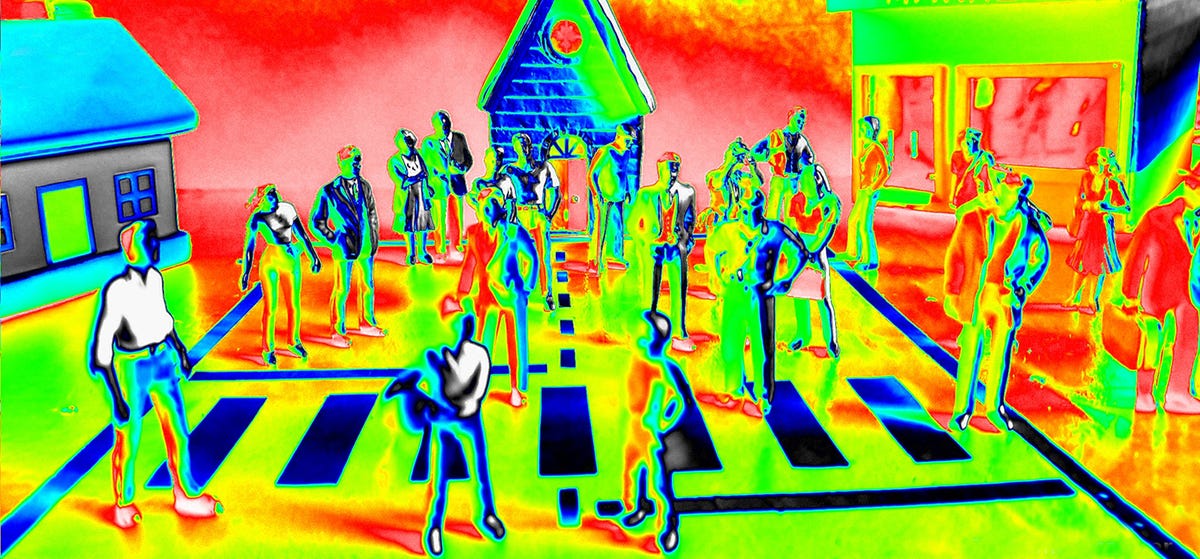

That’s where the unknowns, and the strange complexities of what may come, could bring the biggest changes we need to be concerned with. We didn’t expect social media, back at the dawn of Friendster and MySpace, to be something that would alter the global political landscape. What will widespread adoption of metaverse apps, VR, AR, blockchain technology, and ever-evolving AI end up disrupting that we never expected?

The metaverse also feels like a striving for a new future of social media, or an acknowledgement that the systems we have now may be due to change. Social media, right now, looks like it’s very much in flux. The metaverse isn’t a finished answer yet, or even a coherent fully-fleshed concept, but maybe it’s also an indicator that social media as we know it is going to transform. Maybe the metaverse is what happens to social media when it expands to a far larger canvas.

I picked up Jane McGonigal’s recent book, Imaginable, which details how to think about the future that lies ahead, 10 years from now. The games that futurist researchers like McGonigal use to question large future changes often involve turning assumptions on their heads. What do we assume will be around in 10 years, and what if it isn’t? if the metaverse succeeds, and we end up being able to seamlessly recreate objects digitally, overlay simulations and reality, and blend the two in real time, then what comes next?

Could we eventually split our identities, living in multiple personas at once? Would we embody other people from time to time, or find our identities melting together? Will the future be anything like the nested virtual worlds of Ready Player One, or something far more multichannel and fragmented? Will we have enhanced senses, strange action-at-a-distance superpowers, or will it all seem like our lives on our phones, just far more wrapped around us and ever-present? Will we find AI and ourselves blending and weaving until we’re coexisting with simulations as part of our everyday lives? Will we operate tools remotely, or invent whole new virtual tools that we can’t conceive of yet? Or will the metaverse just be a slow evolution of the internet and our products as we know them?

Watching the recent Industrial Light and Magic documentary on Disney+, I thought of how special effects moved from physical models to digital, and then to more instantaneous digital renderings projected onto real stages, like The Mandalorian‘s production stage called The Volume. The acceleration of the virtual and the real, and the simultaneous overlap, is already here.

From here on in, that coexistence may become even stranger than we can imagine. I’d expect it, since the present is already strange beyond belief.

If so, we’d better start thinking of how to prepare for it – now.

Scott Stein is Editor-at-Large at CNET.