Sudan coup leaders face backlash as internet shutdown continues

General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and members of the Sudanese armed forces shut down the country’s internet this week after announcing a coup on Monday. Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok and several government ministers were arrested as the Sudanese army took full control of the country.

The internet shut down came amid reports of troops opening fire on peaceful protesters, killing at least 11 people and injuring hundreds.

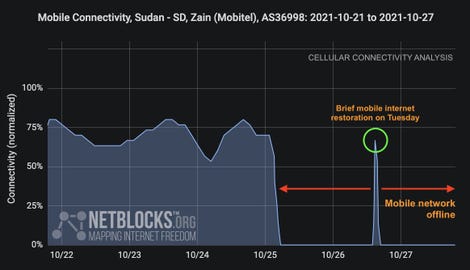

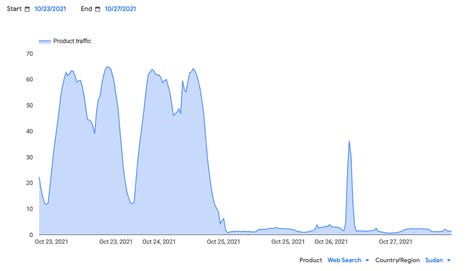

Both Cloudflare and Netblocks reported this week that internet in the country was shut down. Internet blackouts have become the go-to tactic for repressive governments hoping to shield their actions from the outside world. But mobile service was restored briefly on Tuesday, allowing horrifying videos of government attacks on protesters to emerge before it was shut down again.

As of Friday, Netblocks and Cloudflare confirmed that internet in Sudan is still being disrupted, leaving more than 43 million people without access to vital services or ways to communicate with the outside world.

Netblocks

Netblocks explained that this “class of internet disruption affects connectivity at the network layer and cannot always be worked around with the use of circumvention software or VPNs.”

Celso Martinho, engineering director at Cloudflare, told ZDNet that shutting down the internet is not as hard as people might imagine. Martinho explained that the internet is a network of networks, and in the case of a country like Sudan, the networks are their ISPs, identified by their Autonomous System Numbers (ASN).

ASNs exchange traffic between each other, internally and from outside sources like ISPs from neighboring countries, transit providers, or other partners — also known as peering.

“The government can order the local ISPs to stop peering traffic to other entities outside the country. If the ISPs comply, all they need to do is to stop announcing their routes to the outside internet; turning the internet off is a simple configuration change,” Martinho said.

“Citizens in countries going through government-induced partial shutdowns tend to be creative and find ways to access the outside Internet using VPNs or other platforms. However, in this case, we don’t see HTTP or any other type of traffic coming from Sudan.”

Martinho added that Cloudflare has been working with civil society and human rights groups to help call attention to internet shutdowns through Project Galileo and Cloudflare Radar.

“We believe it is important for democratic countries to call out those who shut down the Internet and put diplomatic pressure on them to restore what we believe to be basic human rights,” Martinho said.

Scott Carpenter, the director of policy and international engagement with Google’s open society threat tracker Jigsaw, explained to ZDNet that from conversations with people in other regions, a feeling of complete paralysis takes over when the internet is shut down.

“People have no way of knowing if relatives are safe, for instance,” Carpenter said.

The situation reminded him of when Ethiopia suffered a similar shutdown.

“One person we spoke to feared for his family in Tigray, especially his father who was ill. In his own words, ‘For days I had bad dreams. I couldn’t eat. Couldn’t work. I thought maybe he was gone.’ In other cases, people have been unable to receive proper medical care because they were cut off from doctors in other communities,” Carpenter added.

Internet shutdowns like the one occurring in Sudan take a number of different forms. Some are full-on blackouts while others take the form of chronic censorship, Carpenter said.

The shut down of even one or two services can impact millions, and in many countries “the internet” is nearly synonymous with one or two apps that people use to communicate online every day.

“Internet shutdowns almost always include mobile networks, and sometimes extend to wired lines as well, though those are more important for business users and are often somewhat insulated. In this instance, there appears to be a blackout of mobile networks and most landlines,” Carpenter said.

“Countries have various avenues for implementing shutdowns. If they have only a handful of ISPs and mobile telcos, they can simply ask them to turn off service. In these situations, the telcos have the option to restore access for some individuals, which can allow well-connected individuals to escape the shutdown. Other options are to install specialized equipment in every telco, as has been happening in Russia, or, the bluntest option, to implement shutdowns at the internet exchanges that connect a country’s networks with those abroad.”

When asked what people in Sudan can do to circumvent the blockage or what others outside of the country could do to help, Carpenter and Martinho explained that in the case of total shutdowns like this one, it’s technically challenging to circumvent the block if your provider is a local ISP.

Carpenter said the options for circumventing internet shutdowns vary dramatically by the circumstances. If there’s a total shutdown and you don’t have specialized equipment, then the only off-the-shelf options known are getting a signal from across a border or using SMS-based tools like SMS Without Borders, he said.

“In either case, you’ll be relying on potentially expensive international or long-distance services, and with SMS-based tools, you need to prepare in advance. People with more resources may have a foreign SIM card that continues to work or dial-up modems they can use long-distance with a landline. Options like satellite internet are not widely available yet, nor should we expect them to solve the problem,” Carpenter said.

He urged people outside of Sudan to speak out about the internet shut down and said governments should try to help by providing reliable information about functioning tools and supporting more tools to provide free access.

“In places where shutdowns are regular occurrences, providing journalists and community advocates with foreign SIM cards in advance can sometimes help them stay connected and get information out of the country,” Carpenter explained.

Netblocks noted that Sudan officials have previously blocked social media for 68 consecutive days to shut down protests. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp were restricted from December 21, 2018 to February 26, 2019, the country’s longest recorded network disruption.

There was another mobile internet blackout from June 3 to July 9 in 2019.

The 15-member U.N. Security Council released a statement on Friday calling for the end of the coup and the restoration of the country’s civilian government.